Denizens of the Land of Faerie

Denizens of the Land of Faerie The Folklore of Fairies

“Faeries are the inner nature of the land and a reflection of the inner nature of our souls.”

Brian Froud

Found within these quaint, folkloric depictions, descriptions and written expressions are remnants of the names and titles of beings that are some of the most primal and colossal forces that can be found within the Land and additionally within the Underworld that is known to us in the form of the Land of Phaerie, Elphame, or Elf Home. Within the world of the Witch and within the land of Faerie are chronicles and narratives that parallel one another as they are only separated by the subtlest of guises. Your reading and understanding of these ideas and notions of this mirroring between the worlds is a bridge that unites these two realms and will affect great changes within you when this concept is meditated upon.

For further study and your reading enjoyment the following authors are suggested:

Katharine Mary Briggs (1898 - 1980) — Born in 1898, and daughter of the water-colorist Ernest Briggs, Katherine studied English at Oxford. Katharine was also president and an honorary life member of the English Folklore Society and of the American Folklore Society as well. She also taught and lectured at a number of American Colleges. Her writings include An Encyclopedia of Fairies and British Folktales, The Personnel of Fairyland, The Anatomy of Puck, The Fairies in Tradition and Literature, and Pale Hecate’s Team. Katharine went to be with the Fairies in 1980.

W. Y. Evans Wentz (1878 - 1965) — The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries was Evans Wentz’s first book. Dedicated to two of the people who had greatly influenced him: the poet William Butler Yeats and G. W. Russell (Æ) who was perhaps one of the greatest mystics and visionaries of this century. The theme that runs through The Fairy-Faith is the other world of the Celtic race as this can be discovered in the fairy lore common to all the Celtic countries — Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany, Cornwall and the Isle of Man.

Thomas Keightly (1789 - 1872) — Keightly, raised in county Kildare in Ireland, claimed to read or speak twenty different dialects, this feat helped discriminate between real legends and contrived tales when gathering information for one of his books that would help classify and arrange the denizens of faerie. This in turn, enabled him to collaborate with Crofton Croker in the Fairy Mythology. Also known for being the author of The World Guide to Gnomes, Fairies, Elves and Other Little People.

Lewis Spence (1874 - 1955) — Ranked as a leading authority on the mythology and customs of many varied and ancient cultures. Spence was also a member of the Royal Anthropological Institute. Some of his works include: Fairy Tradition in Britain, Magic Arts in Celtic Britain, and British Fairy Origins.

Lady Jane Francesca Wilde (1826 - 1896) — Mother of Oscar Wilde and wife to Sir William Wilde as well as friend to poet William Butler Yeats, Lady Wilde was an ardent Irish nationalist and her patriotism led her to the study of the folklore of her country. She is most noted for her contribution to fairy-lore with Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms and Superstitions in 1857.

William Butler Yeats (1865 - 1939) — Introduced to the Theosophical Society by friend Charles Johnson, Yeats was a well known poet of the 20th century. His book, The Celtic Twilight, first published in 1893 is a collection of tales about phaerie folk and nature spirits. Yeats’ Celtic influence and love of Irish folklore had a profound impact on fellow occultists.

A

AFANC (Welsh. Rhys, Celtic Folklore): A Welsh water demon who haunted a pool in the river Conway, and dragged down all living things into its depth. He was at length captured through the treachery of a girl whom he loved, and dragged ashore by oxen. The Deluge in Welsh folklore is connected with a monstrous crocodile called Afanc i Llyn.

B

BANSHEE: The banshee is known both in Ireland and Scotland. In Scotland she is sometimes called the Little Washer at the Ford or the Little Washer of Sorrow. She can be heard wailing by the riverside as she washes the clothes of the man destined for death. If a mortal can seize and hold her, she must tell the name of the doomed man and also grant three wishes. She is no beauty, for she has only one nostril, a large, starting out front tooth, and web feet. The Irish banshee only wails for the members of the death of someone very great or holy. The banshee has long, streaming hair and a grey cloak over a green dress. Her eyes are fiery red from continually weeping. In the Highlands of Scotland, the word Banshi means only a fairy Woman and is chiefly used for the fairies who marry mortals.

BAOBHAN SITH (Highland. D. Mackenzie, Scottish Folk Lore and Folk Life): Malignant, blood-sucking spirits, who sometimes appeared as hoodie crows or ravens, but generally as beautiful girls, with long. trailing, green dresses hiding their deer’s hooves.

BARGUEST (Yorkshire. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): A creature of something the same kind as the bogy beast. It sometimes appears in human form, but generally as an animal. In the fishing villages, a barguest funeral is the presage of death. The barguest in whatever form has eyes like burning coals; it has generally claws, horns, and a tail, and is girdled with a clanking chain.

BILLY BLIND (F. Child, English and Scottish Ballads (New York, 1957), Vol. 1): A friendly domestic spirit of the Border Country, chiefly mentioned in ballads. He wears a bandage over his eyes. Auld Hoodie and Robin Hood are perhaps only different names for the same spirit. Billy Blind’s chief function seems to be to give good advice. It was he who advised and helped Burd Isobel in the Ballad of Young Bekie, and it was the Billy Blind whose advice cured the young wife bewitched by her mother-in-law.

BLACK ANNIS (Leicestershire. C. J. Billson, County Folk Lore, Leicestershire): A malignant hag with a blue face and only one eye, very like the Cailleach Bheur in character. Her cave was in the Dane Hills but has been filled up. She devoured lambs and young children.

BLACK DOGS: The black dog is large - about the size of a young calf - black and shaggy, with fiery eyes. It does no harm if left alone; but anyone who speaks to it or touches it is struck senseless and dies soon thereafter. There are stories of the black dog from all over the country. One haunted the guard-room of Peel castle in Man. There are stories about it in Buckinghamshire, Hertford, Cambridge, Suffolk, Lancashire, Dorset, and Devon. There is a very good and full account of black dogs in English Fairy and Folk Tales. In the seventeenth century, a pamphlet of Luke Hulton’s described and attempted to explain the Black Dog of Newgate.

BLUE MEN OF THE MINCH (Highland. D. Mackenzie, Scottish Folk Lore and Folk Life): These men belong to the Minch and particularly haunt the strait between Long Island and the Shiant Islands. They are a malignant kind of mermen, but they are blue all over. They come swimming out to seize and wreck ships that enter the strait; but a ready tongue, and particularly a facility in rhyming, will baffle them. They have no power over the captain who can answer them quickly and keep the last word. Beyond their activities as wreckers, they conjure up storms by their restlessness. The weather is only fine when they are asleep. The islanders think they are fallen angels like the fairies and the Merry Dancers, as the Aurora Borealis is called there.

BODACH (Highland. J. G. Campbell, Witchcraft and Second Sight in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland): The Scottish form of a Bugbear or Bug-a-boo. He comes down the chimney to fetch naughty children.

BOGGART (North Country Spirit. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): He is like a mischievous type of brownie. He is exactly the same as the poltergeist in his activities and habits.

BOGLE: The Scottish version of the Yorkshire boggart, though perhaps less exclusively domestic in his habits.

BOGY BEAST: A general name for boggarts, brashes, grants, and mischievous spirits. Widely distributed.

BRASH: See Skriker.

BROLLOCHAN (J. F. Campbell, Popular Tales of the Western Highlands): Brollochan is Gaelic for a shapeless thing. and it probably something like Reginald Scot’s Boneless. There is a story of one, the child of a Fuath, told by Campbell. It is something the same plot as Ainsel.

BROWNIE: The best known of the industrious domestic hobgoblins. The brownie’s land is over all the North of England and up into the highlands of Scotland. The brownie is small, ragged, and shaggy. Some say he has a nose so small as to be hardly more than two nostrils. He is willing to do all odd jobs about a house, but sometimes he untidies what he has been left to tidy. There are several stories of brownies riding to fetch the nurse for their mistress. The brownie can accept no payment, and the surest way to drive him away is to leave him a suit of clothes. Bread and milk and other dainties can be left unobtrusively, but even they must not be openly offered. The Cornish Browney is of the same nature. His special office is to get the bees to settle. When the bees swarm the housewife beats a tin, and calls out: ‘Browney! Browney!’ until the brownie comes invisibly to take charge.

BROWN MEN OF THE MUIRS (Border Country. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): A sprite of the moors, who guards the wild life, but is malignant and dangerous to man.

BUCCAS OR KNOCKERS (Cornish. Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England): These are the spirits of the mines, something like the German Kobolds. They are said to be the spirits of the Jews who once worked the tin mines and who are not allowed to rest because of their wicked practices. They are, however, friendly to the miners and knock to warn them of disaster and also show what seams are likely to be profitable.

BUG-A-BOO, BUGBEAR, BOGGLE-BO: There is a great variety of names for this bogle, which is generally used to frighten children into good behavior.

BWBACHOD: (The Welsh Brownie People. Sikes, British Goblins): They are friendly and industrious, but they dislike dissenters and teetotalers. Sikes gives an amusing story of a bwbach and his quarrel with a Methodist minister.

C

CAILLEACH BHEUR (The Blue Hag. Highland. D. Mackenzie, Scottish Folk Lore and Folk Life): A giant hag who seems to typify winter, for she goes about smiting the earth with her staff so that it grows hard. When spring comes and she is conquered, she flings her staff in disgust into a whin bush or under a holly tree, where grass never grows. She is the patroness of deer and wild boars. Many hills are associated with her, particularly Ben Nevis and Schiehallion. Her general appearance is terrible and hideous, but in some stories she changes at times into a beautiful maiden. There is a version of the Wife of Bath’s Tale told of her, and she is also the villainess of a story rather like Nix Nought Nothing. At times she turns into a sea serpent. Particulars are given of her in Mackenzie’s Scottish Folk Lore and Folk Life, and she is mentioned in Campbell’s Tales of the Western Highlands.

CAULD LAD OF HILTON: A brownie haunting Hilton Castle who is definitely described as a ghost, and yet was laid, as brownies are always laid, by the present of a cloak and hood.

CA SITH (The Fairy Dog. Highland. D. Mackenzie, Scottish Folk Lore and Folk Life): This is a great dog, as large as a bullock with a dark green coat. He is very like the English Black Dog.

CLURICANE (Crofton Croker, Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland): Another name for the leprechaun.

D

DAOINE SIDHE (Irish): These are the Heroic Fairies of Ireland, very like the Highland Sleeth Ma. May Eve - Beltane - and November Eve - Samhain - are their great festivals. On Beltane, they revel, and - the door being open from fairyland to the mortal world that night - they often steal away beautiful mortals as their brides. On Samhain, they dance with the ghosts. They live under the fairy hills, offerings of milk are set out for them, and in all ways they partake of the fairy nature. Some say that they are the fallen angels who were too good for hell and some say that they are the remnants of the heroic Daanan race.

DEVIL’S DANDY DOGS (Cornish, Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England): A pack of black hounds, fire-breathing and with fiery eyes, which the devil leads over lonely moors on tempestuous nights. They will tear any living man to pieces but they can be held off by the power of prayer.

DOBIE (Border Country. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): A rather clownish and foolish brownie. The dobie is sometimes invoked as the guardian of hidden treasure; but those who can get him prefer the cannier brownie as less likely to be outwitted. Ghosts are called dobies in Yorkshire.

DRACAE (Water Spirits. English. Gervase of Tilbury): It was their custom to entice women to the water by appearing as wooden dishes floating down the stream. When a woman took hold of one, it would resume its proper shape and drag her down into the water to nurse its children. Gervase of Tilbury tells a story of the Dracae and a magic ointment which is very like the Somerset story of the Fairy Midwife.

E

ELVES: The Anglo-Saxon word for spirits of any kind, which later became specialized creatures very like the Scandinavian light elves. Sir Walter Scott, in his Demonology and Witchcraft, describes elves as ‘Sprites of a coarser sort, more laborious vocation and more malignant temper and in all respects less propitious to humanity than the Fairies’. This, however, applies only to Scottish elves, and the little Scandinavians light elves who looked after flowers, and whose chief faults were mischief and volatility, fit the general conception better. In Orkney and Shetland flint arrow-heads are called elf shot, and are said to be fired by the trows, so that trow and elf seem synonymous terms with them.

F

FETCH: A common term for a double or wraith. When seen by daylight it portends no harm, but at night it is a certain death portent.

FUATH (Highland. J. G. Campbell, etc.): The general name for a Nature spirit, often a water fairy and malignant. Urisks were sometimes called Fuaths. The Brollachan was the child of a Fuath.

G

GABRIEL RATCHETS (Northern Counties. E. M. Wright, Rustic Speech and Folk-Lore): The Gabriel Ratchets are like the Wisht Hounds except that they hunt high in the air and can be heard yelping overhead on stormy nights. To hear them is a presage of death. Some say that they are the souls of unchristened children, who can find no rest.

GANCONER OR GACANAGH (The Love-Talker. Irish. E. M. Wright, Rustic Speech and Folk-Lore): The Love-Talker strolls along lonely valleys with a pipe in his mouth and makes love to young girls, who afterwards pine and die for him. In a story quoted in Irish Fairy and Folk Tales, the Ganconers appear in numbers, live in a city under a lough, hurl and play together, and steal human cattle, leaving only a stock behind, just like ordinary trooping fairies.

GLAISTIG (Highland. D. Mackenzie, Scottish Folk Lore and Folk Life): The Glaistig is a female fairy, generally half-woman, half-goat, but sometimes described as a little, stout woman, clothed in green. She is a spirit of mixed characteristics and seems, indeed, to be all fairies in little. She is supposed to be fond of children and the guardian of domestic animals. Milk is poured out to her, and she does something of a brownie’s work about the house. She is specially kind, too, to old people and the feeble-minded. On the other hand, she has darker qualities; there are stories of her misleading and slaying travelers. If the traveler named the weapon he had against her she could make it powerless; but if he only described it, he could overcome her. The Glaistig seems partly a water spirit. She might often be seen sitting by a stream, where she would beg to be carried across. She could be caught and set to work something like a kelpie.

GRANT (English): A demon, mentioned by Giraldus Cambrensis, very like the Picktree Brag. He is a yearling colt in shape but goes on his hind legs and has fiery eyes. He is a town spirit and runs down the middle of the street at midday or just after sundown, so that all the dogs run out barking. His appearance is a warning of danger. Some people connect him with Grendel, whom Beowulf killed; but Grendel was a sea monster.

GWRAGEDD ANNWM (Welsh. Sikes, British Goblins): Lake maidens, not unlike Malory’s Lady of the Lake. They are beautiful and not so dangerous as the mermaids and nixies. They often wedded mortals.

H

HABITROT (Scottish Border. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): The Spinning-Wheel Fairy. A shirt made by a Habitrot was considered efficacious against illness. Habitrot, though very ugly, was friendly to mankind.

HEDLEY KOW (Northumbrian. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): A kind of bogy beast that haunted the village of Hedley. Its great amusement was to transform itself into one shape after another so as to bewilder whoever picked it up; but, like most spirits of its kind, it was fond of turning itself into a horse. Once it assumed the likeness of a pair of young girls and led two young men into a bog. It is rare for a spirit to be able to make a double appearance.

HOB OR HOBTHRUST (Yorkshire and Durham. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): A brownie with most of the usual brownie characteristics, but a specialist in whooping cough. Children with whooping cough used to be brought to Hobhole in Brunswick Bay to be cured by Hob. The parents would call; ‘Hobhole Hob! Hobhole Hob! My bairn’s got kincough. Tak’t off! Tak’t off!’ Like other brownies, he is driven away by a present of clothes.

J

JENNY GREENTEETH (Lancashire. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): A malignant water fairy. She drags people down into the water and drowns them. Her presence is indicated by a green scum on the water.

K

KELPIE (Scottish): A malignant water spirit, which is generally seen in the form of a young horse, but sometimes appears like a handsome young man. A kelpie’s great object is to induce mortals to mount on its back and plunge with them into deep water, where it devours them. A man who can throw a bridle over the kelpie’s head, however, has it in his power, and can force it to work for him.

M

MARA: An old English name for a demon, which survives with us in Night-mare and Mare’s Nest. In Anglo-Saxon, the echo was called the Wood-Mare. In Wales at Twelfth Night, the boys used to carry round a horse’s skull decked with ribbons, which they called Mari Lwyd.

MAUG MOULACH or HAIRY MEG (Highland. Grant Stewart, Highland Superstitions and Amusements): A spirit something between a brownie and a banshee. She haunts the Tullochgorm and gives warning of the approaching death of any of the Grants. She also does brownie work. Maug Vulucht, a spirit very like her, once haunted a Highland household with a companion Brownie Clod.

MERMAID: The mermaid is a much more sinister character than the mild roane, though harmless mermaids have been known. Her appearance and habits are well known to everyone from Scotland to Cornwall. It was considered a certain type of omen of shipwreck for a ship to sight a mermaid. The mermaids sometimes penetrated into rivers and sea lochs as the story of the Mermaid of Knockdolian shows. In Suffolk, indeed, they are said to haunt ponds as well as rivers. Like many other fairies, the mermaids have a great desire for human children. In the folklore of a good many countries, the mermaids and other water fairies are supposed to be very anxious to gain a human soul. Their lives are long, but when they die they perish utterly.

MERROWS (Crofton Croker, Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland): The merrows are the Irish mer-people. Like the roane they live on dry land and under the sea and need an enchantment to make them able to pass through the water. The merrows’ charm lies in their red caps. The merrows’ women are very beautiful, but the men have long red noses, green teeth and hair, and short finny arms.

MURYANS (Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England): The muryans are the dwindling fairies of Cornwall. Long ago they were of more than human size, but for some crime they committed they were condemned to dwindle year by year, till they turned into ants and so perished.

N

NUCKELAVEE (Scottish. Scottish Fairy Tales and Folk Tales): A horrible monster who came out of the sea, half-man and half-horse, with a breath like pestilence and no skin on its body. The only security from it was that it could not face running water.

O

OLD LADY OF THE ELDER TREE (Lincolnshire. County Folk-Lore, Lincolnshire): A tree spirit rather like Hans Anderson’s Elder Flower Mother.

P

PADFOOT (Yorkshire. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): A demon dog that haunts lonely lanes near Leeds.

PEG O’NELL (Mrs. Gutch, County Folk-Lore, North Riding of Yorkshire): The Spirit of the Ribble. She is said to be the ghost of a servant girl from Waddow Hall who was drowned in the river. She is supposed to demand a life every seven years.

PEG POWLER (County Folk-Lore, North Riding of Yorkshire): The Spirit of the Tees. She has long green hair and is insatiable for human life. The frothy foam on the high reaches of the Tees is called Peg Powler’s suds.

PEOPLE OF PEACE (J. F. Campbell, Popular Tales of the Western Highlands): This is the Highland name for the fairies, corresponding to the Lowland “Good Neighbours”. They are much like them in character. Campbell’s story of the Woman of Peace and the Kettle is characteristic.

PICKTREE BRAG (Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): This is a Durham version of the bogy beast. It appears in various forms, sometimes as a horse, sometimes as a calf or dick ass, sometimes as a naked man without a head. It plays all the usual tricks of the bogy beast.

PIXIES OR PISGIES (Devonshire and Cornwall): These are small trooping fairies of which many stories are told by Hunt and Mrs. Bray. There are occasional stories of the brownie type told of them. The white moths that come out in twilight are called pisgies in parts of Cornwall, and are regarded by some as fairies and by others departed souls. In parts, too, they say that pixies are the spirits of unbaptized children.

POOKA OR PHOOKA (Irish): The Irish Puck is in many ways like the Dunnie or Brag. He is in appearance like a wild, shaggy colt, hung with chains. He generally haunts wild places, but in one story, though still keeping his animal form, he works like a brownie, and is stopped in his career of usefulness in the same way by the present of a coat. In this story, like the Cauld Lad, he is said to be the ghost of a servant.

PORTUNES (English): These are a strange kind of fairy reported by Gervase of Tilbury and not surviving in any modern folklore. They came in troops into farmhouses at night, and, after working, rested themselves at the fire and cooked frogs for their supper. They were very tiny, with wrinkled faces and patched coats. It was their nature to do good, not harm. Their only mischievous trick was that of misleading horsemen.

PWCA (Welsh. Sikes, British Goblins): The Welsh Puck is much the same character as in England and Ireland. He likes his nightly bowl of milk, but does not seem to work for it as the bwbachod do. He is specially fond of misleading night wanderers.

R

RAWHEAD AND BLOODY BONES (Yorkshire, Lancashire, and County Folk-Lore, Lincolnshire): A malignant pond spirit who dragged children down into ponds and old marl pits. Sometimes called Tommy Rawhead.

REDCAP (Border Country. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): A malignant spirit who haunts old peel towers and places where deeds of violence have been done. He is like a squat old man with grim, long nailed hands and a red cap, dyed in blood. It is dangerous to try and sleep in any ruined castle that he haunts, for if he can he will re-dip his cap in human blood. He can be driven off by words of Scripture or the sight of a cross-handled sword. In other places, he is less sinister. There is, for instance, a redcap who haunts Grandtully Castle in Pertshire, who is rather lucky than unlucky.

ROANE (The Highland Mermen. Grant Stewart, Highland Superstitions and Amusements): These mermen are distinguished from others by traveling through the sea in the form of seals. In the depths of the sea caves they come to air again, and there, and on land, they cast off the seal skins which are necessary to carry them through water. The roane are peculiarly mild un-revengeful fairies of deep domestic affections, as the stories of Fisherman and the Merman and the Seal Catcher’s Adventure show. The Shetlanders call the roane sea trows, but their character is substantially the same.

S

SEELY COURT (Lowland Scots): Seely means blessed, and this name stands for the comparatively virtuous heroic fairies. The malignant fairies and demons were sometimes called the Unseely Court.

SILKY (Northern Counties. Henderson, Folklore of the Northern Counties): A name for a white lady. The Silky of Black Heddon in Northumberland had one close resemblance to a brownie. If she found things below stairs untidy at night she would tidy them, but if they had been tidied she flung them about. She was dressed in dazzling silks, and went about near the house, swinging herself in her Silky’s Chair - the crossed branches of an old tree which overhangs a waterfall - riding sometimes behind horsemen or stopping them by standing in front of their horses. But on the whole, she belonged more to the class of ghosts than of brownies, for she was laid by the discovery of treasure, which must have been troubling her.

SKRIKER (Yorkshire and Lancashire. Hartland, English Fairy and Folk Tales): A death portent. Sometimes it is called a brash, from the padding on its feet. It sometimes wanders invisibly in the woods, giving fearful shrieks, and at others it takes the form of like Padfoot, a large dog with huge feet and saucer eyes.

SPRIGGANS (Cornish. Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England): Some say the Spriggans are the ghosts of the giants. They haunt old cromlechs and standing stones and guard their buried treasure. They are grotesque in shape, with the power of swelling from small into monstrous size. For all commotion and disturbances in the air, mysterious destruction of buildings or cattle, loss of children or substitution of changelings, the spriggans may be blamed.

T

TOM TIT TOT (Suffolk): The English Rumplestiltskin. He is described as a black thing with a long tail, and sometimes as an impet. Tom-Tit, or Tut or a Tut-gut is a Lincolnshire name for a hobgoblin.

TRWTYN-TRATYN: The Welsh Tom Tit Tot. (Clodd, Tom Tit Tot.)

TYLWYTH TEG OR FAIR FAMILY (Welsh): It is difficult to get a clear picture of the Tylwyth Teg. The name is very much used and for differing types of fairies. They are sometimes described as of mortal or more than mortal size, dressed chiefly in white. They live on an invisible island; they ride about and reward cleanliness with gifts of money; they dance in fairy rings, and mortals joining them are made invisible and carried off forever, unless they are rescued before cockcrow. Others wear rayed clothes of green and yellow, are small and thieving, particularly of milk and children. Unlike many fairies, the Tylwyth Teg are golden-haired and will only show themselves to fair-haired people. The usual brownie story is also told about them. They are very friendly with goats whose beards they comb on Thursdays.

U

URISK (Highland. Grahame, Picturesque Descriptions of Perthshire, G. Henderson, The Norse Influence in Celtic Scotland, etc.): A kind of rough brownie, half-human and half-goat, very lucky to have about the house, who herded cattle and worked on farms. He haunted lonely waterfalls, but would often crave human company, and follow terrified travelers at night, with out, however, doing them any harm. The Urisks lived solitary in recesses of the hills, but they would meet at stated times for solemn assemblies; a corrie near Loch Katrine was their favorite meeting place.

W

WEREWOLVES: The earlier attitude to the werewolf is more tolerant than that towards the loup-garou in seventeenth-century France. Giraldus Cambrensis has a story of a priest called to shrive a dying woman in wolf form. It was thought in Ireland to be a curse that might fall on any man for a certain number of years. In the medieval romance of William and the Werewolf, the wolf is a good character and the victim of enchantment.

WHUPPITY STOORIE (Scottish. Chambers, Popular Rhymes of Scotland): The name is apparently taken from the circular scud of dust upon which fairies are supposed to ride. It was the name of a Scottish Tom Tit Tot fairy, and also of the fairy on one version of the Habitrot story.

WILL O’ THE WISP: This is the commonest of the many popular names for the ignis fatuus. It is sometimes described as the soul of a wicked man, but more generally as a kind of pixy.

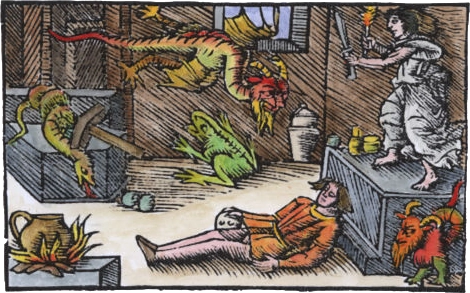

Gilpin Horner

I have a tale to tell you, it hap’d near Todshaw-Hill,

I only speak the truth now so believe it if you will.

As evening came upon us, John Moffat and meself,

We heard a wee high voice, like that of some wee elf.We were hindering our horses, so they’d not wander far,

Tied up their legs right loosely, so not to leave a scar.

The crescent moon was rising, casting ‘round it’s glint,

When John and I heard a pitiful cry, the words of “Tint, Tint, Tint!”There was no body standing there, no body far or near,

John says, “What devil’s tint you? I tell you now come here!”

I wish old John were silent, I wish he’d held his tongue,

Out of the bloom and out of the broom, a goblin man had sprung.Gnarled were his arms and legs and most twisty was his face,

Right frightened I and John both were in that lonely, wooded place.

I longed for home that instant, I ran downhill and fled,

My conscience named me coward as I left my friend for dead.I left the horses, left the pack, I left it all behind,

Though once I had to turn to look and see what I might find.

John Moffat lay upon the ground, the goblin on his chest,

I’ll never forget that awful sight in all my days of rest.At last I came upon the hedges to my own cottage row,

Leapt them all quite nimbly and into the house I go.

And in the corner laughing, calling out to my surprise,

It was that goblin, Gilpin, seen with my own two eyes!He layed in for the winter, he layed in as you please,

He pinched the children black and blue and was a wicked tease.

He brought no boon upon us, he had no gifts of fairy,

He dined upon our own sweet cream and emptied out the dairy.I watched him in the snowfall eating bread and jam,

I heard him mutter in the night, he called out Beteram.

John Moffat’s son Will struck him, he struck him out fullsore,

But that peccant little imp Gilpin stayed fast behind the door.He came out in the twilight, when the cows were heading home,

He came out then, and only then, when night began her gloam.

He leered at all the milking maids, and even my own wife,

I swear this now, on poor old John and even ‘pon my life.T’was early in the springtime, when clovered was the ground,

There at the dusk one evening I heard an odd, strange sound.

A voice so shrill and loud it raised hackles cross my skin,

I heard it once, no, twice, and then yet one final time again.“Gilpin Horner, Gilpin Horner, Gilpin Horner!” Peter Beteram did cry,

I heard this in the meadowland, I heard this by the by.

The voice it carried on the wind, across the close of day,

And Gilpin Horner up and states, “Tis me, I must away.”His Master’s voice an echo now and empty is the stool,

Where Gilpin Horner sat and laughed and made us all the fool.

He went not by the chimney, not even by the door,

That hob-goblin Gilpin Horner shall trouble us no more!© Dawn R. Jackson